(by Kaiser Fung)

A reading of the arguments by Kosara and Gelman/Urwin (PDF link) reveals one essential dividing line between statistical graphics and infoviz: the division of labor between the graphics creator and the reader. The infoviz designer expects readers to work the data while the creator of statistical graphics works on behalf of the reader.

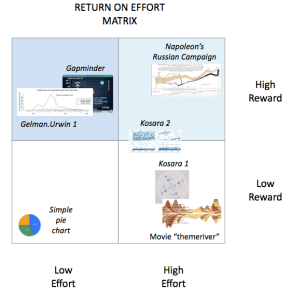

To capture this difference, I would like to introduce a new metric for evaluating graphics: the return on effort. Effort, conceptually, is the amount of work a reader needs to do in order to understand the graph. Such work includes reading the axes, the scales, the legends, the text, and sizing up the columns, the bubbles or other forms, and understanding the context of the analysis, such as the population and the metrics, and grasping the general question being addressed, and so on. The return on effort is the amount of pleasure gained from the time spent on learning how to read the chart.

Even acknowledged “perfect” statistical graphics can require a high degree of effort. For example, a newcomer to the famous Napoleon’s march through Russia chart (Tufte’s version here) must take time to absorb the multiple dimensions and admire the efficiency of presentation. In this case, the reward justifies the level of effort, and the return on effort is high.

In the matrix shown below, the famous chart occupies the top right quadrant indicating high effort, high reward graphics.

Many statistical charts demand little of readers; the advice is to avoid low-reward charts like simple pie charts. The justly-celebrated Gapminder is a set of statistical charts with rich insights needing little effort. (or see my review here.) Focusing on Tufte’s data-ink ratio will generally push charts to the high reward half of the matrix.

By contrast, it appears that most infoviz charts fall into the high effort, low reward region. Kosara’s two charts (PDF link) require readers to interact with the data, and discover the hidden insights. The much circulated “themeriver” graphic of box office sales over time also places stringent demands on the reader who is intent on learning

something from the data.

I hope that as the field of infoviz develops, the graphics would move into the high reward region. The opportunity is there, as the availability of more data allows us to learn complex patterns, which in turn would require more sophisticated graphics. But readers will not be willing to expend effort if the reward is not sufficient.

(Kaiser Fung is the author of the Junk Charts blog, and Numbers Rule

Your World.)

Interesting conversation. I addressed the question of learning to understand the language of graphics in blog excerpts of my Master’s capstone, “Information visualization: a new visual language.” You can find the 8 part discussion (including pluses, minuses, semiotics, cognitive fluency, etc.) here: http://carlacasilli.posterous.com/

It’s interesting that this topic is about return on effort. I just arrived at this blog through a Google “buzz” from a fellow scientist, and I haven’t been a regular reader here.

This looks like a fascinating discussion, but I’m unable to follow along without a relatively massive expenditure of effort — there’s no link to the arguments of Kosara or Gelman/Urwin; the png showing sample graphs is too small, even when expanded to full-size, for me to understand what the “Gapminder” chart display or why it’s celebrated (and there’s no link for me to get a better understanding of it); a link to Tufte’s data/ink ratio would be appreciated; et cetera. I could, of course, google all of these things, but that’s quite a lot of effort.

The effort/return quadrants don’t just apply to graphs; they apply to any source of information. I’m sure that understanding the references in this post would be quite rewarding, but, in this case, the effort required is so unnecessarily high as to be off-putting.

+1 for adding links to the examples used in the matrix

@toddt and @Peter: I’ve added the links for your convenience. Thanks for proving my point that charts that require lots of effort on the part of readers are unlikely to succeed!

Who is the reader? That matters a lot.

Statistical charts often demand little attention of *expert* readers, who have seen the same type of chart many times before.

But while a Q-Q plot is immediately legible to me, to a layman it’s no clearer than the themeriver.

It sounds to me like Kosara’s chart is not intended to summarize a conclusion that’s already been reached. It’s designed for someone who hasn’t made a conclusion yet and *wants* interaction with the data. In this case, it can be high-effort + high-reward for the analyst, a producer who is also the reader, even if it might be high-effort + low-reward as a summary for the reader who just wants to get to the point.

Jerzy, good point. Having been in both the academia and the industry, I think people in academia may tend to focus on the chart content than on the story to be told. After all, in research, charts may help the researcher to find hidden conclusion or to test hypotheses. Andrew Gelman got to the point in his posting.

In businesses (used in general sense), usually the purpose of a chart or a graph is to help the presenter tell a story. The focus shifts from the content or intellectual curiosity to the goal, i.e. the audience. In this instance, who is the reader: the chart creator, the story teller, or the audience? Please note that in most companies, the chart creator, usually a data mining, statistics, or operations research analyst may be different from the story teller, usually a business analyst, an account executive, or a manager. Contrary to what Enrico Bertini says, in business presentations, a confusing graph may not invite more reader involvement. It may confuse the presenter and the audience, and hence make the story unappealing to the audience. It is wasted effort with negative return. A confusing or purposeless chart may turn off the reader and the audience.

To summarize, if infoViz targets academia and research, perhaps the more the content the better. If it is to be adopted by businesses, it has to be able to simplify information and help the story teller get to the point with less effort. By experience, vendors of simpler infoViz solutions are preferred to those with complex content overload systems.

Felicien Kanyamibwa, PhD.

http://www.aroni.us